I have written about many projects that use an Android Phone or Tablet to command an ESP. There are several ways to do that.

You can use a dedicated APP written in Mit's App Inventor like this story explains: http://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2018/02/wifi-voice-commander.html or this story https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2018/01/wifi-relay.html

You can also have a web-page on the ESP that has buttons and sliders which can be accessed from any browser including your phone's or tablet's like this story (programmed in LUA) https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2016/05/esp8266-controlled-ledstrip.html or this story https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2016/08/rain-sensor-using-esp8266.html or the Relay server https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2016/09/esp-relayserver.html and of course the obvious thermometer: http://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2017/11/oh-no-not-another-wifi-thermometer.html

All these projects have one thing in common. The Android phone or Tablet sends data to the ESP. It is never the other way round.

Searching the internet I did not find any project in which an ESP8266 send data to an Android device where the Phone or Tablet is used to process the data or just to display it. And for a certain project (still in devellopment) that was just what I needed.

So I had to find it out for myself. And actually it turned out to be much easier as I expected.

There are 2 sides to this story The ESP side and the Android side.

The ESP side

I wanted a quick and dirty solution so I used ESP-Basic for this. If you want an introduction to lean to work with ESP-Basic read this: https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2017/03/back-to-basic-basic-language-on-esp8266.html

The basic (pun intended) point is that we want to have the ESP react on an incoming request. I did that before when I let the ESP react on a message send to it from IFTTT in this story: https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2017/05/google-home-and-esp8266.html

And actually I did the same in Arduino language (C++) in this story:

https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2018/01/wifi-relay.html

Both these stories let the ESP react on an incoming request but that is not what I wanted. I wanted the ESP to send data to the device that send a request. And that involves just a light modification of the code.

msgbranch [mytestbranch]

wait

[mytestbranch]

a = a+1

myreturn = "test number " & str(a)

print myreturn

msgreturn myreturn

wait

The msbrach just waits till the ESP receives a message. It is not important what the contents of the message is. We do not even check it.

When a message is received the program jumps to the [mytestbranch] routine.

In there the variable "a" is increased and a return message is send to the device that send the request.

Piece of cake.

The Android side

The Android program is made with Mit's APP-Inventor. If you do not have any experience with writing APP's for Android please take a look at APP-Inventor. It is easy to use and works like Scratch on the Raspberry or other block-oriented programming environments.

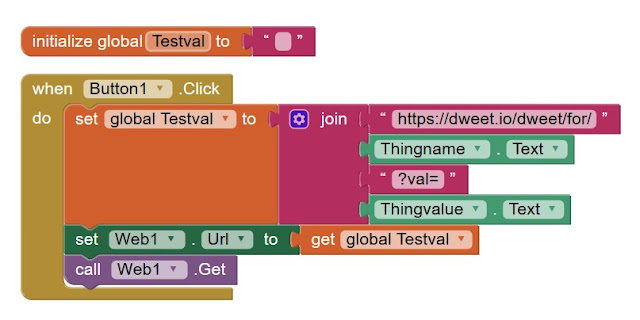

Start with designing a screen that contains a button and a label.

The label is the small green dot just below the button.

Now switch over to the block side and here is the program:

This part has a few flaws. It works but remember this is only a proof of concept.

The first block defines what happens when the button is clicked. And that is easy. A 'get' request is send to the ESP's IP adress. Finding the ESP's IP adress can be done in several ways. In ESP basic:

print ip()

will do the trick. Another way is to open your router's web page and look there for the IP number of the ESP. I described that in several stories here on this weblog. For example in this story:

https://lucstechblog.blogspot.nl/2018/02/esp-voice-control-with-esp-basic.html

You could make this program universal by adding a text field in which you can type the IP-adress. That way this small program can be usefull for getting information from a number of ESP's. Just be creative.

The next block is activated when a request has been received and a return message has been send.

The text in the label is then set to the response.

That is all folks.

Real world

The Basic program prints on the screen of it's web page what is send to the Android device. As you can see I have pressed 8 times on the button on my Android Phone.

The Android device, which is my phone but could also be a tablet or whatever, displays the last received data from the ESP.

Expanding the code

Here are several ideas to expand the code.

- Like stated above add a text field in the Android program/screen so you can fill in the ESP's IP-number

- Send multiple data to the Android Device

- Make this a two way conversation. For example the Android Device asks for certain information like a number, temperature, sensor data or whatever and let the ESP respond with the right information.

- Let the Android Device switch on a lamp, pump, motor etc and let the ESP respond if it is done so you are sure things work as you'd expect.

I think you can come up with a lot of projects and ideas for this.

Till next time

Have fun

Luc Volders